Nobody’s Home (transcript)

Housing blight — concentrated areas of vacant properties — is harming communities across the country and posing a risk to the financial system. But governments seem powerless to turn it around. We're finding out why. A special 10-part series by American Banker.

Nobody’s Home (Transcript)

Housing blight — concentrated areas of vacant properties — is harming communities across the country and posing a risk to the financial system. But governments seem powerless to turn it around. We're finding out why. A special 10-part series by American Banker.

By John Heltman

“Do You Hear Me?”: How Blight Is Hurting America

JOHN BULLOCK: Good evening everyone, thank you for coming out, if you do not already have a seat, there is seating in the balcony so please feel free to grab one. Again, this is the Baltimore City Council Housing and Urban Affairs Committee, thank you for coming out this evening. The hearing tonight is on Council Resolution 170037, dollar house program …

HELTMAN: On a crisp evening last October, the Baltimore City Council gathered to consider a resolution concerning one of the city’s most visible and enduring problems — thousands of homes left dilapidated and empty — housing blight. This is City Councilman John Bullock.

BULLOCK: I know there’s so much interest in this subject, demonstrated by the attendance here this evening. We know that vacancy and blight is a huge challenge here in Baltimore City, we have thousands of vacant properties littering our city, and we have to be creative in our approach.

HELTMAN: But for many city residents, patience is running thin.

RESIDENT 1: I live in southwest Baltimore. You want to talk about blight — blight leads to crime. Blight leads to people just not caring anymore because they’ve given up hope. Do you hear me?

BULLOCK: Yes, ma’am.

RESIDENT 1: Do you understand what I’m saying?

RESIDENT 2: I wonder if you have the political will to do the right thing. Because you’ve inherited a legacy. You’ve inherited 50 years, 60 years of doing nothing in regard to housing in this city, fundamentally.

HELTMAN: It’s not like there isn’t any development in Baltimore, and it isn’t like nobody is building housing. But no one is fixing the vacant houses, they say. None of that development is reaching their communities.

RESIDENT 2: Access to capital is the question, and guess what? Redlining is still alive and well. We’ve got to be the lightning rod in this nation, because every urban city in this country, through conspiracies, find themselves with thousands of abandoned houses. Don’t tell me that’s not by design. We’ve got to break out of that genocidal approach to people who want to live, and have a right to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.

HELTMAN: Baltimore is the biggest city in Maryland, with a population of over 600,000. It also has an estimated 16,000 vacant houses and another 14,000 empty lots, many of them concentrated on the same streets, or even taking over entire city blocks.

Maybe you know that. You may also know that other cities have the same problem. And if you know those things, it probably wouldn’t surprise you that concentrated vacant housing brings with it a host of secondary problems, such as crime, economic stagnation, unemployment, lack of business investment and falling property values.

And here’s the thing — the vacant houses themselves aren’t really the problem at all. The problem is the hazards that vacant houses pose to people who live nearby.

What we call “housing blight” brings a whole range of negative associations for people who live there, at least statistically — everything from lower educational attainment, lower lifetime earnings, greater risk of health maladies like depression and diabetes, and even lower overall life expectancy. From what I can tell, there doesn’t seem to be a metric that social scientists use to measure quality of life that isn’t made worse by vacant housing.

And this isn’t just a Baltimore thing, either. All across the country, vacant housing is a growing part of the landscape, from Indianapolis…

RTV6 NEWSCAST: The Indianapolis Fire department announcing today that it fought 34 fires in 19 days, 15 of them in vacant homes and buildings. In the process, seven firefighters have been hurt. That trend continuing, overnight …

HELTMAN: … to Cleveland …

Fox8 CLEVELAND NEWSCAST: Heartbroken loved ones gather on Fullerton Avenue and east 93rd street in Cleveland Wednesday evening … to remember 14 year old Aliana Defreeze. Sunday police discovered her body inside this vacant home. “She was just a baby …”

HELTMAN: … to Albuquerque …

KRQE NEWSCAST: … there are dozens of vacant homes in this neighborhood that neighbors would love to see something done with, and now a city task force has proposed more than 20 ideas — some of which could give the city more power in addressing this issue.

HELTMAN: And that doesn’t even mention the countless rural communities all over the country that are struggling with too much vacant housing.

But if this problem is so important, and if it affects so many communities across the country, then why isn’t anybody talking about it? What can be done to solve it? Why can’t these citizens have the communities they want? If these communities need help, who or what is going to bring it to them? Or is this just the way it is?

My name is John Heltman, and I’m a reporter with American Banker, an independent newspaper that covers the banking, housing and payment industries. I am also, like those voices you just heard, a resident of Baltimore. Over the course of this podcast, I’m going to unwind the threads that lead to vacant housing, and try to find out the causes of — and potential solutions to — the challenges that it poses. Why are these houses vacant in the first place? What have authorities tried to do to address these concerns? And what actually works? How do you take these neighborhoods, these communities that have been struggling so hard for so long, and make them into the kinds of places that people want them to be? Is that even possible?

From American Banker, I’m John Heltman, and this is Nobody’s Home.

HELTMAN: So let’s start by defining the issue. What is vacant housing, or blight? It might seem obvious, but there’s more to it than you might think. For starters, there are a lot of different words out there that describe what we’re talking about. “Vacant housing” is a little too broad, because an empty house that is up for sale or a vacation house doesn’t bring down house prices or correlate with the kinds of quality of life issues that we’re talking about here. Housing blight, or urban blight, or just “blight”, is a word that is used a lot, but it brings some baggage with it as well. “Blight” literally means a disease, so when you apply that word to housing, it makes it sound like the neighborhood is diseased or infected, and connotes that it needs to be cleansed. But, keep in mind, these are places where real people live and that real people care about, and people who live in those communities don’t necessarily see their neighborhoods that way.

One definition that I found for blight is a quote “physical space or structure that is no longer in acceptable or beneficial condition to its community,” which kind of works, because the community is the arbiter of what is blight and what isn’t.

So concentrated vacant housing, or blight, or whatever you call it — what does it do? Why does it matter? Why should you care? I asked this guy …

GOLDSTEIN: I’m Ira Goldstein, and I’m president of policy solutions at the Reinvestment Fund.

HELTMAN: The reinvestment fund is what’s called a Community Development Financial Institution, or CDFI, based in Philadelphia. CDFIs are banks that are specifically chartered to serve communities that other commercial banks don’t serve. In addition to making direct investments in low- and moderate-income areas, TRF — as they are known — also researches patterns in those areas to find ways to ensure their investments have the biggest impact.

GOLDSTEIN: I describe us to people who are not necessarily steeped in the ways of financial institutions as a lending institution with a public purpose. So we lend and invest to create affordable housing and child care centers and arts and culture space and fresh food retail and health centers, and all the things that low-wealth people in places need to be able to have at a vital and equitable and healthy shot at a good life.

HELTMAN: What role does housing play in giving people that shot at a good life? The costs to the cities are fairly easy to understand, from the loss of tax revenue to the costs associated with boarding up and policing vacant properties. But the costs to residents and investors in places where vacancy has taken hold are also acute, and occur in surprisingly predictable ways.

GOLDSTEIN: For your audience, bankers, they know that you know anybody who wants to get a mortgage is going to have to get an appraisal. When the appraisal is done, the presence of vacant properties detracts from the value. And so there's a pretty good literature out there as well that points to the, essentially, the economic costs in the value of a home for literally every vacant property within, roughly speaking, a tenth of a mile from the … property that is being considered. So, you know, depending upon what era you're looking at, it could be you know a percent or you know or more for every vacant property within a subject property. So if you think about a neighborhood in Philadelphia where a row, a row house neighborhood where within a tenth of a mile you got you know a thousand properties and there's 200 of them vacant.

HELTMAN: That’s 20%.

GOLDSTEIN: That's a lot. Exactly. Exactly. So that is the kind of economic cost. Now you have the social costs and there what you're thinking about is what is it like for my children to have to walk up and back to school past a vacant and abandoned property. What are the safety issues? What are the fear issues? What are the … what are the things that impinge upon our ability to create a vital community on our block? How do you know who your neighbors are? You know all those kinds of social sorts of things that really attach to the kind of physically blighting influence of these properties. So there really are, I would say, a whole host of different kinds of effects beyond the economic that really attached to these vacant properties.

HELTMAN: Those effects of vacant housing —and, by extension, substandard housing — are actually measurable, and can be surprisingly specific. There are psychological effects that also negatively affect people who live close to it, and sometimes in surprisingly specific ways. The most obvious effect of vacant housing is that it makes people feel worse about the place they live — when your home is seen to have little value, you value it less yourself, and other people do too. A study of low-income women published in the Journal of Urban Health in 2011 found that disrepair can be linked with instances of psychological distress. Several studies have shown correlations between poor housing conditions and increased rates of asthma, heart disease, diabetes, elevated lead levels, stunted growth, venereal disease and even life expectancy.

But the most well-documented correlations between vacant housing and public health are because of the increased instances of crime, and those crimes are typically perpetrated against people in those neighborhoods. One challenge here, however, is that there’s a chicken and egg problem. Is there more crime because the surrounding homes are vacant or are there more vacant homes because there is more crime?

This question has not been definitively resolved, because the two are so closely linked.

Here’s the thing — it almost doesn’t matter, because the solution is the same regardless. One study from 1999 suggested that blight and crime have to be controlled in order for any more constructive gains can be made in a neighborhood’s schools or local economy. Another study in 2016 agreed, saying that in order to reverse cycles of violence, the conditions that spark criminal behavior have to be seized for any future interventions to be effective. Whether blight causes crime or crime causes blight is beside the point — you can’t solve one independently of the other. That bears repeating: if you want to solve crime, you have to solve the issue of vacant housing. You can’t improve conditions in blighted neighborhoods without solving blight.

So how widespread is blight? How many vacant homes are we talking about?

GOLDSTEIN: I don’t think anybody really knows. Most places, most municipalities around the country, couldn’t tell you, within thousands, how many they have. The best bet that you have is the last community survey for the nation, says that there are 16.8 million vacant properties, vacant housing units around the country. Of that 16.8 million that the census identified, these are housing units now, you have about 4 million or so that are for sale or for rent or about to be occupied … and about 5 million that are those seasonal, so what you’re left with is, you could say this, is about 5.8 million that are “other vacant” to the census. What does that mean? It means it’s not the identified categories, but our experience in places like Camden or Baltimore is, a lot of times that “other vacant” category really are the properties that you would identify as those abandoned ones.

HELTMAN: 5.8 million vacant houses. As you heard, that’s an estimate, and it’s the best estimate we have. But Goldstein said it’s probably low.

GOLDSTEIN: The census doesn’t get all of those, so we really believe that 5.8 million is probably a really big underestimate of the abandoned properties. At some point they don’t send census forms or census takers, you mentioned Baltimore, some of the properties that you can see through the roof. They don’t send census forms to those places. So the 5.8 million really is a pretty big underestimation of that. But the long and the short of it is, cities don’t know.

HELTMAN: Part of the reason why we don’t really know how many vacant and abandoned homes there are is because there isn’t a readily identifiable way of knowing when a vacant home becomes a blighted home. It’s a process, and homes that are abandoned or in the process of getting abandoned tend to arrive that way gradually and only become counted when they either are cited for property code violations, are foreclosed on or become the ward of the city or the state. Different cities have more or less streamlined processes for this, Goldstein said, but in all cases the process is imperfect.

GOLDSTEIN: It’s like fish through a stream. These properties are kind of coming in and going out, and when you take that snapshot you know what it is in that moment. Five days later you could have 100 other properties come on and 100 other properties go off.

HELTMAN: In Baltimore’s case, the 16,000 vacant homes I mentioned earlier is the number of “uninhabitable” homes in the city — that’s a designation the city makes for properties that not only do not have anyone living there, but are unsafe for anyone to live there at all. But when I talked to Amanda Davis at the University of Baltimore’s Jakob France Institute — they study neighborhood trends in the city — she said that you have to look at more than just the house itself to figure out if it’s vacant. She looks at all kinds of different metrics to find out where vacant housing is getting concentrated.

DAVIS: So, some of the indictors we collect around those topics might be the number of vacant and abandoned buildings, 311 calls for service … dirty streets and alleyways, trash collection. We also collect, in addition to the city’s metrics on vacant buildings, we also collect undeliverable mail from the post office. That is an indication that nobody is living in that building. Sometimes just looking at one indicator alone is not enough to tell a story of a neighborhood, so you have to look at a number of indicators to sort of paint a picture of what’s going on in a neighborhood. Whether the population is growing, whether it’s declining, how many vacant buildings are there, we have to look at tall these indicators together.

HELTMAN: So if you look at that data, where do you find concentrated vacant housing? Is this limited to post-industrial cities? Is this an east coast thing? Is it primarily in cities?

GOLDSTEIN: I believe it is everywhere to a different degree, and for different reasons and in different concentrations. So, places like rust belt cities, Philadelphia, Pittsburgh, Baltimore, Detroit, Milwaukee — places that over the course of the last 50 or so years lost 30-50% or more of their population. So when you have that kind of loss, it’s simple to understand why you have that kind of vacancy and abandonment.

In other kinds of cities taken out of the rust belt phenomenon, you’re looking at a variety of causes that attach to housing obsolescence, to disinvestment, to disasters to a variety of other things that combine to create these vacant property areas.

DAVIS: There are some common themes that cross geographies. A housing market, like any consumer market, is supply and demand. So when you’ve lost a large amount of population from the city, there’s less demand to fill those vacant properties.

HELTMAN: While vacant housing may look the same in different places around the country, it isn’t all necessarily caused by the same thing. Many cities lost population in the latter half of the 20th century, with former city residents moving to the suburbs. De-industrialization and the decline of factory jobs played a role in many places; natural or manmade disasters played a role in others. But the underlying result is effectively the same — people were moving out and no one was moving in to replace them. And this happened over decades, involving millions of people and millions of households.

HELTMAN: Is blight kind of like a workable proxy for other kinds of societal effects, like crime and economic sort of disinvestment, lack of economic activity – if you solve blight, is it fair to say that you can maybe make a dent in some of these other kinds of problems?

GOLDSTEIN: I think you absolutely can. I’ll give you a concrete example: the City of Philadelphia had a program a couple of years ago where, where what they were essentially doing was making some creative use of some state law changes and local municipal building code changes, provisions. And what they were doing was actively going out and citing properties that did not have workable windows and doors. And the maximum penalty that could be assessed for those properties was $300, per opening, per day. So if you think about a two-story row house, you have two windows on the second floor and two windows on the first, and a door, right?

HELTMAN: And there’s two in the front, and …

GOLDSTEIN: … and two in the back as well. If you had one of those properties and you were missing a couple of those things, you could be fined $300, $600, $1,200 per day. What we found was, where the city was proactively going after these things, it really had a significant and positive unlocking effect on the value of property around it.

HELTMAN: So if lots of vacant homes are bad for communities — they bring down property values, they attract illegal activity, they discourage investment, etc. — then why don’t cities just knock them down? Well, they do. All the time, by the thousands. In fact, in 2015 Maryland Governor Larry Hogan, a Republican, and Democratic former Baltimore Mayor Stephanie Rawlings-Blake announced a nearly $700 million plan, known as Project CORE — which stands for Creating Opportunities for Renewal and Enterprise — to tear down some 4,000 properties over four years and subsidize redevelopment of those sites.

But if this was just a matter of tearing down vacant buildings — or setting aside money to tear down vacant buildings — then this would be a really short podcast. The problem is that at the same time that housing blight is weighing down neighborhoods in Baltimore and elsewhere, people are having a harder and harder time finding an affordable place to live. Nationwide, almost a quarter of all renters spend more than half of their income on rent — a statistic that has been fairly consistent over the last several years. Those burdens are especially severe among middle- and working-class households, and Baltimore is no exception to those pressures. The rent, to borrow a phrase, is too damn high.

That brings us to the subject of that city council hearing we heard earlier. A group of citizens want to bring back a program from the 1970’s called the “Dollar homes” program, where the city sold a property to people for a dollar and provided financing for them to fix it up. They don’t want those homes torn down, or at least not the ones that can be repaired. If the city and state spent some of the money dedicated to Project CORE on financing renovations, they argue, prospective homeowners could rebuild those homes themselves, or with assistance of certified professionals. One contractor named Ronald Stewart spoke at the hearing, and he said that the problem isn’t that there isn’t too much housing, and it isn’t too expensive to rebuild a lot of these houses. And if the properties are torn down and redeveloped, the new properties are never going to be within the financial reach of the people who live in the neighborhood.

RESIDENT 3: It’s not that we’re asking for an exorbitant amount of money to remodel houses that should be remodeled anyway. The people that live there shouldn’t be forced to move so that developers can come in and build bigger houses and sell them to people that have money. We don’t have the money. We don’t have the money to buy the houses that they’re building in my neighborhood, two blocks from my house. I think we’re making this too complicated. We’re making this too complicated. A person wants to buy a house, you’re willing to sell it to them for a dollar, you give them a loan, they get a contractor, they have a house. It’s as simple as that.

HELTMAN: This is the question. Why can’t these cities fix themselves? What’s stopping them? And would a modern Dollar Homes program be part of the solution? We’ll find out next time, on Nobody’s Home.

Dead Pledge: The Rise and Fall of Urban Homesteading

HELTMAN: This looks like the place. That looks like Ms. Van Allen.

HELTMAN: There was a program that Baltimore spearheaded in the 1970s and 1980s that was supposed to stem the rising tide of vacant housing. It was called the dollar homes program, and the idea was to allow prospective homeowners to acquire a vacant property for a dollar or some similarly nominal fee, and then give them low-cost financing to renovate the property, subject to city inspections and under a specific deadline. The idea was that prospective homebuyers could rehabilitate a vacant house on the city’s rolls, bringing them into the city and turning an otherwise unproductive property back to productive use. And I’m here today to meet someone who participated in that program. I wanted to learn what her experience was like, and whether that program from 30 years ago holds any clues into how to address vacant housing today.

From American Banker, I’m John Heltman, and this is Nobody’s Home, a podcast about vacant housing, our communities and the financial system.

HELTMAN: I met Catherine Van Allen …

HELTMAN: Good, how are you?

HELTMAN: … and this is the home she renovated, near Hollins Market in southwest Baltimore.

HELTMAN: I didn’t think I would beat you here, but…

VAN ALLEN: That’s all right. This snow kind of put me a little bit … nice to meet you.

HELTMAN: Nice to meet you, too.

VAN ALLEN: Let’s see here. Well I’ve just had it recently renovated, as you can see, because I thought it’s the time to sell it, but I think what I’m going to do is rent it for another couple of years …

HELTMAN: Catherine said she used to shop at Hollins Market every day, and worked a few blocks away at Bentalou Elementary School, now named Mary Ann Winterling Elementary.

HELTMAN: What kind of teacher were you?

VAN ALLEN: I was a kindergarten teacher. What the heck is going on? I think I’m picking the wrong ones. I worked there for 20 years.

HELTMAN: When we get inside, the house looks great. In the years since she renovated the property she has rented it out as two separate apartments, but for a time she ran a store of her own out of the first floor.

VAN ALLEN: This is where I had my storefront.

HELTMAN: Right.

VAN ALLEN: Catherine’s Junk, QUE That was about right.

HELTMAN: That was, uh. So you had a store here?

VAN ALLEN: Yeah.

HELTMAN: What did you sell?

VAN ALLEN: Just … stuff.

HELTMAN: So, like cheese and …

VAN ALLEN: No, just antiques and things.

HELTMAN: Oh, I see.

HELTMAN: She tells me the house was built in 1855, and before she got it, it had been a laundromat. But in the 1970s the owners died and their children didn’t take the property, so it was vacant for about ten years before she got a hold of it. And there’s a story behind that, too.

VAN ALLEN: I camped out for a week on the sidewalk in front of the convention center. A friend of mine, a set of twin brothers and I, met each other here in Baltimore, and they wanted a house and I wanted a house, so we found Rehab Express.

HELTMAN: Okay. What’s Rehab Express?

VAN ALLEN: Rehab Express was one of those programs, after the Dollar Houses. I had bid on a dollar house, and came in second on Montgomery Street.

GEORGE: Hello!

VAN ALLEN: This is George. George is also a rehabber from Baltimore.

HELTMAN: Oh, neat.

HELTMAN: George had rehabilitated a vacant rowhome in Federal Hill about ten years ago, but knew Catherine when she was rehabbing this house, which, as she said, she camped out for a week in order to buy.

VAN ALLEN: What I did was, my mother lived in Washington, and I would drive to see her all the time. And I kept coming by the convention center. We looked at the thing in the paper, Rehab Express, and they were going to sell the properties for $200 each.

HELTMAN: So a big markup from the dollar homes, I guess.

VAN ALLEN: Yeah. Still not bad. Still not bad. And at that time I think I was making about $10,000 as a teacher in Baltimore City, and you know, that wasn’t a whole lot, but I was single and didn’t have any encumbrances or anything.

HELTMAN: This was in 1982. She said she and her friends had gone over the lists of available properties on Rehab Express for months, scouting out more than 100 different locations, at least from the outside, before they settled on this one and another down the block. They wanted to take on these projects together, and they figured if they were close to each other it would make it easier to help each other out. After they settled on this house, she was driving by the convention center and saw that someone else was already waiting for the Rehab Express event the following week. So she got in line. And then she waited.

VAN ALLEN: It was the summertime, so I could, you know, not go to school. And so I, we just started camping out there. We camped out, and finally we put up a tent, and, you know, they moved us up to the side and put up a porta potty out there, you know, people were going in the bushes . One of the brothers would come down, you know, they both worked.

So they opened the doors after a week. They had different tables where, you know, you would give them your information, and you would tell them which property you were interested in, and they were, you know, “Yes we have that one” or “No we don’t have that one, that one’s been taken off the market.”

HELTMAN: She said she got the title to the property that day, for the price of $200, with the stipulation that she had to renovate the property within one or two years. But that same day, she got to see the house she waited in line for a week for the opportunity to buy.

VAN ALLEN: You know, they gave us the key to the property, and I mean, the key to the property was the key to a padlock that was chained on the door.

HELTMAN: Right, right.

VAN ALLEN: And so, uh …

HELTMAN: What kind of shape was it in?

VAN ALLEN: Oh, god. Bad. It had been abandoned for ten years, and the roof was falling in, and …

HELTMAN: So you could, like, see through the roof?

VAN ALLEN: Oh yeah.

HELTMAN: Like, vermin? Like, what else?

VAN ALLEN: Oh yeah.

HELTMAN: Was there still stuff here? Like old laundry or whatever?

VAN ALLEN: Oh no. It was just abandoned, you know? The steps were kind of rickety and you sort of had to be really careful going up the steps and things like that. I actually think I crawled in from the back.

HELTMAN: So you didn’t even bother with the padlock.

HELTMAN: But she spent the next few years fixing the house up, doing a lot of the work herself.

VAN ALLEN: I dug 18 inches down in the basement, because it was so short. It was dirt.

HELTMAN: Oh so there wasn’t even a slab down there. Wow.

HELTMAN: But eventually she finished the house, and by that time she had met a man in the neighborhood, and he and his teenage son moved in. A few years later, they had another child of their own and decided they needed more space, so they moved to Ten Hills, a neighborhood on the western edge of the city. She kept the house and has rented it out ever since. But she says the experience of renovating the house had an empowering effect that just buying a house wouldn’t have given her.

VAN ALLEN: It was the foot up that I needed, you know, to have something for me, something that I owned. I had a car, you know, and I rented apartments. But this was mine. You know, it made a difference in how I saw … uh … my future.

HELTMAN: That program — the dollar house program and the similar programs that followed — was an early idea of a young housing commissioner.

ROBERT EMBRY: Robert C. Embry. Well, I was a city councilman and then housing commissioner from 1968 to 1977.

HELTMAN: He is now president of the Abell Foundation, a nonprofit organization based in Baltimore. He said when he became the housing commissioner, he was just 30 years old, and he had a dim view of the prevailing attitude toward neighborhood revitalization — which was then known as “urban renewal.”

EMBRY: My view of urban renewal and public housing programs was that it tore down blighted properties and replaced them with new properties. And after I became a housing commissioner various advocates in the community that were concerned with historic preservation sensitized me to the value of preserving the unique historic fabric of the city, as opposed to replacing it with things that were generic to any American city.

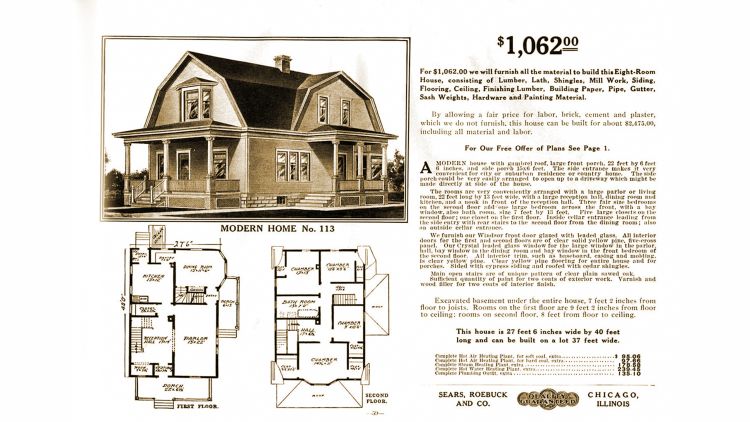

HELTMAN: He got the idea for Dollar Homes from a similar program initiated by the mayor of Wilmington, Del., in the early 1970s. It was the early days of a concept in urban planning at the time known as “urban homesteading.” The idea was based on the 19th century model of frontier homesteading, where someone could acquire land for free from the government if they committed to improve it and live there themselves. This was the model that settled the West. The Dollar Homes program was Baltimore’s version of this old paradigm, but the urban version posed its own challenges.

EMBRY: One was the need for financing. That, if you were a vacant house by definition is a house that nobody wants to invest in — that's why vacant. And it means that it costs more to fix it up than it's worth when you fix it up. And so no lending institution would responsibly lend on a property that wouldn't appraise for the cost of fixing it up, because of the mortgage or the cost … the amount of the mortgage. So we needed to set up a financing mechanism. And secondly we needed to create an office that would help potential homeowners — who overwhelmingly had never rehabilitated a house — to find an architect and find a contractor and then supervise construction and make sure that the money was spent on fixing the house. You know there were draws, progress draws, monitored by somebody making sure the work you were contracted for is actually done.

HELTMAN: The money for the program came from two places. The city got the capital to provide the low-interest redevelopment loans to the homesteaders by issuing a municipal bond to the public, then taking that money and lending it to the borrowers, who in turn paid it back at some nominal markup. The administration of the program came, at least in part, from federal dollars the city received from the Office of Housing and Urban Development, known as HUD.

Congress liked the idea as well, and in 1974 passed a bill that allowed HUD to transfer properties it had in its inventory to cities for use in their homesteading programs. And that inventory was mostly foreclosed loans through the Veterans Administration or the Federal Housing Administration. Over the course of the next five years, HUD transferred some 2,300 properties in 22 cities this way.

And then, suddenly, it was over.

HELTMAN: So what happened to the program?

EMBRY: So, it ended. I left to go to work for the federal government in 1977 and the city ended the program. Why it ended it, I don't know. One change was the Internal Revenue Code was amended in 1986 to say that you could not issue tax exempt bonds for housing redevelopment other than for moderate- to low-income recipients so that placed an income limit on the borrower.

HELTMAN: That eliminated the city’s ability to raise bonds to pay for renovations, except if the borrowers earn a low- to moderate-income. That’s a technical term, which HUD defines as less than 115% of an area’s median income, adjusting for family size. But the city can’t rehabilitate a vacant house at a price that someone in that income bracket could afford.

EMBRY: I mean, it's not a low-income housing program. Public housing, for instance, in Baltimore the average income of a public housing resident in Baltimore is $13,000 a year. If you say that your mortgage should not be more than three times your annual income you're talking about a mortgage of $40,000. To rehabilitate a house in Baltimore, depending on how big it is, ranges from $150,000 up to $3- or $400,000. So it's not a program for homeless people much less low income people. But for somebody making $80- or $90,000 depending on the House, the city, you know, you can make a loan to them and defend that that they could pay it back.

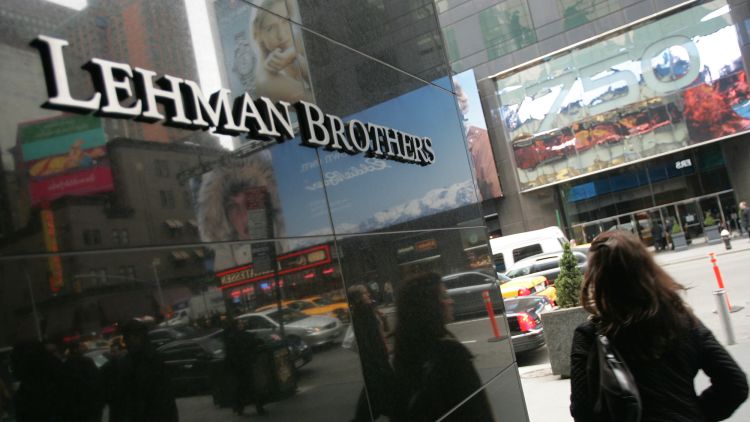

HELTMAN: This is as good a place as any to lay out a primer of how mortgage lending — and by extension, banking — works. Everyone understands a loan — I borrow money from a bank, credit union or another financial institution because I need it but don’t have it on hand. The institution that lends the money to me does so based on the expectation that I will give it back at some later date. And as most people are probably aware, lenders charge interest, which is just extra money for the trouble of giving the loan in the first place. Interest is generally some percentage of the original loan amount. For example, 1% interest on a $100 loan is $1, 2% is $2 — you get the idea.

The idea of a mortgage goes back centuries — the word is actually a combination of old French words meaning “dead pledge,” because the terms of the pledge are terminated, or die, either when the payment has been satisfied or the borrower fails to pay. A mortgage is also a prime example of a secured loan, which means that if the borrower fails to live up to the terms of the deal, the lender will take the property as collateral, since technically it was their money that purchased it in the first place.

When a borrower buys a house and secures a mortgage, the most important and often tedious parts of the process is agreeing on a price. Under normal circumstances, a seller offers a home for a price and a buyer will agree on that price or enter into negotiations. But the mortgage lender also has an interest in that price, since the property is acting as the collateral for the loan.

So what is a house worth? It’s worth what someone is willing to pay for it. That’s it, there is no objective way of pricing homes, because unlike almost everything else we buy, each home is different. You can have two identical houses next to each other and they will be priced differently, if for no other reason that they have two different buyers with two different offers at two different times.

But no one really thought about why people value homes the way they do, at least until the financial crisis. I asked an expert …

GARRIGA: My name is Carlos Garriga, I'm an economist here at the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis.

HELTMAN: … about how the financial crisis got people interested in how housing markets work.

GARRIGA: They view that as just another market, like automobile. And after the crisis, it became clear that housing was slightly different and it was more important. After the credit meltdown, you know, it became obvious that, you know, studying what's going on in that market and what was driving prices up or prices down was something that it was needed to be understood. It was not as automatic as, you know, studying the durable … durable market — so where, you know, production is more of a driver of cost, right? I mean you have you know in a lot of things that are manufactured, the cost of those things are, you know, basically driven by you know production costs and sales and things like that. Whereas is in the housing market, you know, a lot of the things that you're creating is existing inventory of homes. So the, you know, the construction and the production of new homes only represent a small fraction of the market. So a lot of value is driven by other characteristics than the production itself — you know, location, attributes to certain neighborhoods, and so on and so forth. And any homes might not be able to compete in some of these niche markets. So where new homes are built may be different from where old homes are built. So that's why you know housing markets, I would argue, are subtly different.

HELTMAN: This may seem like a detour, but a lot of what makes concentrated vacant housing so hard to reverse is that it is, or at least can be, a representation of a collective attitude about a place, both by people who live there and by people who don’t. Those vacant houses are places where nobody lives, but they’re also places where everybody has chosen not to live. How do you value a place like that? How do you value the home next door? And while we’re thinking about it, why does anyone live anywhere? How do people decide what any home is worth, collectively, through markets? These questions occupy an almost philosophical intersection of people’s values and feelings — which can be based on almost anything — and hard numbers and prices. And those hard numbers can have a big impact on the whole neighborhood, or even whole cities. And it puts vacant properties in a particularly challenging bind. If you ask a banker …

JUSTIN WISEMAN: Justin Wiseman, associate vice president and managing regulatory council the Mortgage Bankers Association here in Washington, D.C.

HELTMAN: … or, in this case, someone who represents them, they will say …

WISEMAN: … one of the issues with that is you have to get an appraisal.

HELTMAN: An appraisal, by the way, is where an expert comes and inspects a property and assigns a price. Back to Justin …

WISEMAN: Because the banks want the appraisal and it's the improvements and the any area and things like that. So to be sort of one of the first people to turn around a block or to get into a vacant or abandoned property surrounded by other vacant properties ... It can be hard to find that sort of intersection of where the improvements and appraised value make sense when you look at the other vacant or abandoned properties.

HELTMAN: In other words, even if you fix up a vacant house and make it livable, you would be left with a house that is worth less than the materials and labor used to fix it up. It’s like making a sandwich that is worth less than the bread, meat and cheese are worth on their own. And banks can’t make that loan, in part because banks themselves don’t actually own most of the mortgages they make. They sell them, primarily to Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac. Those government-sponsored enterprises turn them into securities — specifically Mortgage-Backed Securities, or MBS — which in turn are bought by investors. If a bank can’t sell a mortgage, it has to hold it itself, on its books.

WISEMAN: If you can't get it off your books, you have to put the risk on your books. I mean, it's sort of the basic equation of mortgage lending — you either sell it into an MBS or you hold it on your portfolio. And if there's not an investor or an MBS aggregator that has an appetite for what you're trying to sell, and the only real recourse — and this is obviously simplistic — is to put it on your books.

HELTMAN: He went on to say that, in neighborhoods where housing blight is prevalent, the problem isn’t that banks won’t make a loan. The problem is that they can’t.

WISEMAN: I think — and this is going to sound somewhat vague so I apologize in advance — but I think looking to mortgage lending to solve the kind of community problems that lead to widespread blight is probably too shortsighted, kind of, a view. If there are people that want to buy in the neighborhood, I think you would see lending. If the neighborhood or the property for whatever reason isn't attractive to people who want to get the loan on it, that's sort of a second order effect. It's kind of down the chain, right? And absent community-wide development initiatives or things that make the area attractive, or you remove restrictions or environmental conditions that make it unattractive, it's hard to see mortgage lending as the solution to those problems.

HELTMAN: Which is why Embry, the housing commissioner who created the Dollar Homes program, said the entire point was to get whomever had the wherewithal and desire to rehabilitate a vacant property and live in it to do so, not just low-income borrowers. One underreported fact about the program — and it’s a hugely important one — was that they had no defaults.

EMBRY: We had a 100% payback on the mortgages, so we didn't take any losses. And yes, we made money yes on the property tax yes on saving police and Fire boarding up costs, but we also just made one percent we were tacking one the interest on the mortgage.

HELTMAN: Another underreported fact about the program is that relatively few homes were ultimately rehabilitated. Embry doesn’t know how many there were.

EMBRY: I don't have the slightest idea.

HELTMAN: And estimates range from as few as 200 to as many as 600, though those numbers may not include Rehab Express or other subsequent programs. But in the context of at least 16,000 vacant homes — and probably many thousands more — even giving vacant properties away can’t address the scale of the problem. And vacant houses in and of themselves are not necessarily the issue, Embry said.

EMBRY: I mean I don't particularly care about vacant houses. I mean, I would rather house not be vacant. Where I care about this simplistically and the people that are there, and the disparity in America between the African-American population and the Caucasian population in terms of income in terms of jobs in terms of education, crime, so forth. And you're very familiar with the average net worth as a black American being like one 10th to one 20th of the average white American, and most African-Americans having no cash to fall back on if there’s an emergency of one kind or another. That's what concerns me. And yes I'd rather the House be not vacant but that's really a symptom of a larger problem.

HELTMAN: Another under-reported aspect of the dollar house program is that, in many cases, the changes that it brought to certain communities were short-lived. The housing program helped Hollins Market for a time. But now, there are still whole blocks of vacant houses and storefronts and lots.

VAN ALLEN: This neighborhood, when I was rehabbing this house, was a lot of really young people. You know, and a good stretch of people, you know, in different age groups, who were artists, and, you know, wanted to … some people, a fella who had come down from New York NS he opened up a wonderful restaurant right down the street called the Cultured Pearl. But you know, there were a lot of different kinds of people that worked in the neighborhood. But, you know, it was a very artsy community. You know, and then I think what happened was, people started having children, and they moved further out, you know, further out, you know, either to the edge of the city where the schools were better. I mean, my children all went to city schools, but I could choose which city school they went to. That middle school change is a really tough one. Because, you know, West Baltimore Middle was out there, and I didn’t want my children to go to that School. You know, I knew the educational situation, you know, so I took them to Canton Middle School, where Craig Spielman was the, uh …

FRAZIER: I think that’s where they, that’s where it kind of failed, where the Dollar Houses failed.

VAN ALLEN: Yeah.

FRAZIER: Was that they had, you know, it was sort of aimed at, you know, independent white folks who are in careers, wanting a house, you know, like yourself but also people with dreams, and artists, and so on.

VAN ALLEN: Right.

FRAZIER: So it was sort of aimed at them. But as you say, when they had kids, and they had other options, um, you know, for the health of their family — there weren’t other people that were, say, came from the neighborhood that had rehabbed these houses that would be staying there.

VAN ALLEN: Right.

FRAZIER: And so it just, when it went down, it was just like a balloon. You know, losing air. That, if it had those kinds of legs to it, it wouldn’t have collapsed.

HELTMAN: So if the dollar homes program and the urban homesteading movement didn’t solve blight, what are people doing now to create a better, more sustainable solution? I mean, how do you bring a neighborhood back from decades of disinvestment? Can you? We’ll find out next time, on Nobody’s Home.

Building From Strength: Inside Cities’ Battle Against Blight

STOSUR: I’d like to introduce myself. I’m Tom Stosur, planning director. And we’re here tonight with a whole bunch of planning staff and partners to give you a good flavor of where we’re at with the final draft of the Green Network Plan that’s been two years in the making. Next …

HELTMAN: This past March I went to a public meeting in Barclay, a neighborhood in central Baltimore, to hear about something called the Baltimore Green Network. The network is an outgrowth of more than two years of effort from the city planning department and other neighborhood partners, and the idea was to incorporate parks and trails and green space into the city’s landscape.

When you look at what vacant housing does to a community, one of its most immediate and measurable — and compounding — effects is that it can bring down neighboring home values. That leads to more vacancies, which lead to still lower values, which leads to more vacancies. It’s a cycle, and once it takes hold, it can be hard to reverse. And it gets even harder to reverse the longer it sets in.

DUFF: In neighborhoods that are convenient to things that middle-class people want to do, you can get positive feedback loops …

HELTMAN: Yeah.

DUFF: … such as you find in Canton or Hampden, most of D.C. and things like that. Other places you have to work at it. And you might have to mount a professional effort. My colleagues and I mount professional efforts for a living.

HELTMAN: That’s Charlie Duff, president of Jubilee Baltimore. They take on real estate development projects aimed at mounting, as he calls them, professional efforts, to both reverse the fortunes of neighborhoods beset by vacancy and to keep vacancy from taking hold in the first place.

DUFF: Because of us, there are no vacant houses on the north side of Patterson Park, or on the east side of Patterson Park. And I think, if it hadn’t been for us, there would be 5,000 more vacant houses in east Baltimore than there are today.

HELTMAN: He says the Patterson Park Community Development Corporation bought, renovated and sold some 400 houses adjacent to the park in the early 2000s, while another nonprofit, Friends of Patterson Park, focused on revitalizing the 137-acre park itself, improving amenities and bringing in new activities. Those efforts were bolstered by an unrelated boom in real estate in Canton, a waterfront neighborhood to the south of the park.

DUFF: We couldn’t have done Patterson Park if Canton hadn’t got hot.

HELTMAN: Vacant housing is something that is a lot easier to prevent than it is to reverse …

DUFF: Yes.

HELTMAN: … and I don’t know if that’s something that people think about when they think about their policies.

DUFF: They never think about it.

HELTMAN: From American Banker, I’m John Heltman, and this is Nobody’s Home, a podcast about vacant housing, our communities and the financial system.

HELTMAN: Baltimore, like many cities and other communities around the country, has a surplus of vacant houses — about 16,000, according to Baltimore’s housing commissioner …

BRAVERMAN: Michael Braverman I'm the director of the Department of Housing and Community Development in Baltimore City.

HELTMAN: But that isn’t a static inventory — it’s not the same 16,000 year after year. Some get renovated or demolished, but new ones come on to the city’s rolls to take their place.

BRAVERMAN: There are some number that are renovated each year and that number is significant, something roughly a thousand a year. There's some number that are demolished every year — that number is also significant, about 400 properties a year. But that said, the net number stays … there's no net change to the number. It stays roughly the same, because we are continuing to see depopulation in some markets and the trends that have led to this state we're in now are continuing in some markets and being, and there ... and we're seeing sort of increased occupancy and renovation and others, but we are running stable roughly 16,500. We're making progress in different … in different parts of, say, significant progress areas of the city where the numbers of vacant buildings are netting down by numbers like 30, 35%. Then there are other parts of the city where it is as much an effort as we are employing to combat the number of vacants, new ones are rising.

HELTMAN: The city has a program, known as Vacants to Values, that operates as a kind of clearinghouse for its vacant property inventory. Part of that program is aimed at conveying properties to buyers and developers, but it also has provisions meant to keep current homeowners in their homes.

BRAVERMAN: To do weatherization, to do slip and fall, to do the first step to put a roof on. All of these are important parts of keeping residents who are housed in their homes, and to be there to benefit from what we hope would be transformative change in their neighborhoods.

HELTMAN: But while it can be easier to stabilize a neighborhood that is on the verge of a vacancy problem, it still isn’t easy. And whether an intervention is being mounted before a neighborhood gets blighted or afterwards, certain conditions have to be present in order to turn around a neighborhood’s narrative.

DUFF: The two things you can do, if you’re too late for prevention, one is to rebuild. And if you’ve got a minute I can show you a good example of that. There’s only one, but since we catalyzed it, it’s three minutes away from here, I can show it to you.

HELTMAN: Sure.

DUFF: You can rebuild them, but only if you’re either really lucky, really rich, or both. Let’s take a ten minute drive.

HELTMAN: Sure.

HELTMAN: So we took a drive down to Station North, just a few blocks away. Station North, like much of Baltimore, is a former industrial area, dotted with old factory buildings. One of them is the cork factory, which produced the first bottle cap. And like other industrial neighborhoods in Baltimore, it started declining when the factories closed and nothing came to take its place. As we drove down Calvert Street, Charlie said half of the occupied homes we saw were vacant; an abandoned school has been restored and is now a public charter Montessori school; the old abandoned factories are now occupied as apartments and artist studios.

DUFF: This is a neighborhood that, ten years ago, was 56% either vacant houses or vacant lots. What happened? Well, first of all, it was in a good location. It was next to Mt. Vernon, and Mt. Vernon turned around and began to grow. It was just south of Charles Village, Charles Village turned around and started to grow. Third, it was within walking distance of MICA, and MICA went from 900 students to 2,600 students, and students take up space, and create vibe. And then finally, it’s within walking distance of Penn Station, and MARC service got good and Penn Station commuting caught on. And all of that wasn’t enough.

HELTMAN: This is an important part of how governments approach redevelopment, and it can get overlooked. Michael Braverman, the City Housing Commissioner, said that cities like Baltimore have finite resources to put toward housing projects, and almost as a rule the more vacant housing there is to address, the fewer resources a city has to address it.

BRAVERMAN: The mayor and the City Council, our local government is as firmly committed to supporting the residents in every neighborhood. That means new resources. So with new resources you know and new and standing up the department of housing community development as an independent agency to address this particular issue, you know, they're doing this because they want significant improvements and reinvestment in some of our historically disinvested neighborhoods. And that's working with markets, building from strength, not expecting transformative change where you know it is literally would be a stretch, but in areas where it is possible but needs that additional investment in that application of technical expertise and partnering to get it done.

HELTMAN: When he says “building from strength,” what he means is investing in projects in areas close to stable housing markets and anchor institutions. And that isn’t a new or unique idea employed by Baltimore — it’s the standard approach to redevelopment. If a block of vacant houses is one or two streets away from a neighborhood with a vibrant housing market, or a baseball stadium, or an arts college, or a transportation hub, those vacant houses are more likely to find buyers. Over time, the city’s investments in those borderline neighborhoods can build upon each other, and stable neighborhoods will begin to knit each other together.

But that triage approach to investment has a dark side, which is that is basically acknowledges that, for those parts of the city that aren’t near a stadium or arts college or transportation hub, help is not on the way. At least not right now.

BRAVERMAN: We expect to see significant declines and significant improvements in many neighborhoods in the city. But I think you know the larger problem really is one that you will take a longer period of time to see changes in. And that wouldn't be for lack of trying on the local level and lack of partnership with the state. This is the state and local government doing everything we can with the resources that we have to address the problem. It's simply not enough.

HELTMAN: Station North is an example of a place where the city and partners made an investment that has begun to reverse a housing market. Being close to robust housing markets and anchor institutions and transportation made it a promising candidate. But with a 56% vacancy rate, what it didn’t have was a housing market of its own. If someone wanted to buy a home — especially a vacant or abandoned home — they would face the same fundamental challenges that dollar home buyers face, particularly with financing.

The city, along with community development groups like Charlie’s, sought to prime the real estate market’s pump by building a rent-subsidized artist’s colony in Greenmount West, known as City Arts. And that was in 2010.

DUFF: Our lenders thought it would lease up in ten months. It leased up in ten weeks.

HELTMAN: Wow.

DUFF: We thought, you know, out of 69 apartments, we thought that half of them would move out, so we built, at the end of the first year — that’s sort of standard — so we built a waiting list of 35 people, and then when the leases came due at the end of the end of year one, instead of having 35 people move out, we had five people move out.

HELTMAN: So the city built another one, City Arts II, which was completed in early 2017. That had a similarly robust demand, Duff said. And the local real estate market has also started to revive, with remodeled homes selling from $160,000 to upwards of $300,000. And then he showed me this.

DUFF: These are the first new, unsubsidized houses built in this neighborhood since the 1800s.

HELTMAN: Wow.

DUFF: And I’m going to their open house on Monday afternoon. Do you want to go?

HELTMAN: Yes, I do.

DUFF: Good.

HELTMAN: And so I did.

HELTMAN: I’m sated at the moment, but I might trouble you for a glass of water in a minute. So this is Station North.

FRANK: This is Station North, and this is Greenmount West within Station North …

HELTMAN: That’s Sam Frank, co-partner of Four Twelve Development, who built the house I’m visiting on a Monday afternoon last October.

HELTMAN: So tell me about …

FRANK: Yeah. So what you’re looking at here … Shea, this is John, he’s from the Sun, Charlie …

HELTMAN: Oh, sorry, I’m with a group called American Banker.

FRANK: American Banker.

HELTMAN: Yeah.

FRANK: Cool. So that’s great.

HELTMAN: That’s Shea Frederick, the other co-partner at Four Twelve. And what they’ve built is a new rowhome in Greenmount West — that is, not a rehab of an existing rowhome, but new construction altogether. As Charlie said, it’s the first market-rate new construction in the neighborhood for more than 100 years. And rehabilitating vacant houses is what they were doing before they decided to embark on this project.

FRANK: Alright, so the story here is that we … Shea had been working on vacants, and I joined him as a carpenter’s aide, and we were kind of looking for a project that would help us ramp up and get both of us kind of full-time jobs, because it would have to be significant enough where both of us could work on it. So we found a plot of land which was four subdivided lots that were just grass lots. And we purchased it and we sourced a bank loan for it, and then we just started building.

HELTMAN: Sam said that the home we’re in is the model home, and once they sell it, they will have enough capital to build out similar townhomes on the remaining three lots. And the house, by the way, looks really nice. It’s got a modern kind of feel — lots of exposed brick, open concept, stainless steel fixtures, that sort of thing.

FRANK: A couple of things are really interesting about this project. One, lots of reclaimed materials. So we used this company called Brick and Board a lot. They’re kind of like Second Chance, but more local, and they’re hiring guys, disenfranchised guys that, you know …

HELTMAN: Need some work?

FRANK: Need a chance. And what they do is deconstruction, where they take homes, rowhomes, and basically instead of demolishing them, they pull them apart piece by piece, save the materials and then sell them to builders.

HELTMAN: Huh.

FRANK: So the wall that you’re looking at behind you, this is actually made with bricks dug out of the ground from the original homes that were on this plot of land.

HELTMAN: Huh.

FRANK: Combined with some bricks from those guys, which are, you know, from a rowhome in Baltimore.

HELTMAN: Right, right. So it’s all locally-sourced, as it were.

FRANK: Yeah, like, completely.

HELTMAN: Some of the labor was locally-sourced, as well. Four Twelve hired laborers from within the neighborhood to work on the house. This is Sam’s partner, Shea.

SHEA: We have a local crew of, uh, I guess interns, you’d call them.

HELTMAN: Right.

SHEA: They live within the neighborhood, within at least six blocks.

HELTMAN: Is that common?

SHEA: And uh … no, it’s not. But it was just, uh, something that we felt like we should do.

HELTMAN: Yeah, yeah.

SHEA: Just put some money, like, directly into the neighborhood.

HELTMAN: Yeah. And some training, too.

SHEA: And training, yes. That’s part of it, too. These guys learn basic carpentry skills. So the steps were all done by our local guys. A lot of the painting and the trim. And even things like door hardware installation. They got trained on it and we just let ‘em loose.

HELTMAN: Remember when Sam said they got a loan to build this house? I talked to the woman who gave them that loan.

DANA JOHNSON: I'm Dana Johnson and I'm a managing director for Maryland and Washington D.C. at the Reinvestment Fund.

HELTMAN: That’s the same Reinvestment Fund that you heard from in the first episode. Dana runs their Baltimore office, and she said she worked with the city and other nonprofits to rebuild subsidized houses in the neighborhood.

JOHNSON: As the vacancy rates started to come down and that the housing price of the sale prices started coming up, you know, you start to see a lot more private activity that doesn't need subsidy anymore. You know, if you can sell a house for well — and you mentioned the Four Twelve folks — you know if you can sell a house for, you know, $280,000 or, you know, whatever, like yeah, you don't need … you don't need you need or need to wait around for, "I've got to get this tax credit and I got to get this funder," to you know, whether it's a state grant or whatever you know cobbling — I mean these things take forever to cobble together all these different sources and when you don't need that, it starts to move more quickly.

HELTMAN: She said that sparking a market for real estate in an area that doesn’t have one is hard, and it takes subsidy. But the Reinvestment Fund — like the government and all the other potential investors in underdeveloped neighborhoods — have to be judicious about where they apply their dollars.

JOHNSON: I think there's a way of being smart about how you use subsidy. And being smart about how you approach reinvigorating the market, that, it's not about, well, “We need, you know, $50 million or nothing.” You know and I think lots of folks here in Baltimore have been kind of taking that kind of strategy of, you know, yes, initially you know figuring out where are those blocks, you know, that can be restarted, that are close enough to areas of strength that you can build off of that strength, and use subsidy and theoretically, over time, when you do the next block or the other half of the block you need less subsidy because you've now you've got properties that have appraised and sold. And so you know the … the lenders — whether they're us, or banks — start seeing that you know this is these are sort of financeable transactions that the economics do work. And so, over time, you know, the level of subsidy in those redevelopments can go down over time as you're building off strength. Now, if you start in like you know the toughest block in the toughest neighborhood, you know, it's very hard to figure out how to how to capture real estate economic strength. There's not a lot to grab onto.

HELTMAN: This strategy of having neighborhoods grabbing on to each other — as if to keep them from some kind of an abyss — is just one of countless images that get used to describe something that is actually quite abstract. One of the blunter examples is calling a neighborhood “good” or “nice” versus “bad” or “rough.” Depending on who says it, those words can be code for “black” or “white;” “rich” or “poor.” But there are things that a nice neighborhood has that a rough neighborhood doesn’t, and vice versa. One of those things a “nice” neighborhood has is the absence of vacancy — or at least the ability to withstand it. One of the properties of a “rough” neighborhood is that few businesses will risk their investment there. And if a city wants to change those perceptions — to change the market — it can be costly, and time consuming, and it may not even happen at all.

And it also leaves those neighborhoods for which interventions are not being mounted out on their own. That doesn’t mean no redevelopment is happening — it just means that redevelopment is being done on a small scale by individual investors, who may or may not have a vision for where they want the neighborhood to go.

JOHNSON: You know on the one end of the spectrum, there's a lot of what they call “hard money” lenders that are out there that are. You know they're not — they're not really like underwriting the transaction. They, you know, they don't sort of get in the weeds of people's … they're almost like, they're lenders, but they're almost sort of play that kind of equity-like role but they that — they charge a lot of money. They'll still charge 12% interest. And so you know they have that sort of kind of money running around, and how do you connect to that. You know, that can be...

HELTMAN: I mean, is this — are these banks? Or...

JOHNSON: No, they're, like, individuals. Yeah. Yeah. Not firms but like...

HELTMAN: You know, a guy who says "Hey, you want some money?"

JOHNSON: Some of that. Yeah I mean I've heard you know different sort of varieties of that. But or just like you know, wealthy individuals sure I have. I'll take a flier and give you know you give me 12 percent and yeah there's a chance that like I never really money back. But yeah.

HELTMAN: But if I do, I get 12% interest.

JOHNSON: Yeah exactly. I mean the risk-reward, all that. So there's kind of that kind of money that you know smaller, you know, folks doing one or two houses — it's, there's not a lot of process around it so it makes it easier to use. Now, of course, you know, if you're if you can't sell the house and you're hanging onto debt at that kind of interest rate, like, that it really makes things challenging.

HELTMAN: The fact that these neighborhoods don’t have access to the traditional housing market — you know, realtors, comparable homes on which to base appraisals, and, for the most part, prospective owner-occupants — makes things challenging for developers who might build.

That isn’t to say people don’t buy and sell these properties, because they do. Some people buy vacant homes and flip them — that is, fix them up well enough that they can sell them for a profit. Some people buy houses and rent them for as long as they can, even if the accommodations are substandard. And there’s a tactic known as buy-and-hold, where someone buys a vacant house for, say, $5,000 or $10,000, and neither flip them nor rent them. They just … have them. And they hold on to them indefinitely, hoping that the neighborhood might get hot someday and they can sell high.

But what about the people who live in these neighborhoods? What do they think about this strategy, about building from strength? Well, that’s why I went to that Green Network meeting that you heard earlier. The city’s plan is to launch a number of pilot projects in the near term, including things like bike paths and parks and community gardens. And these pilots are slated to move forward in places that have vacant housing issues; neighborhoods like Druid Heights, Broadway East, and Sandtown/Winchester. But those are neighborhoods that abut sources of strength, like the stronger housing markets of Reservoir Hill and Bolton Hill or the Johns Hopkins Campus.

And at least some of the folks I talked to didn’t seem very impressed.

RESIDENT: How do I feel about it? I think it was short-sighted. I think they had their preferred way they wanted to go. Their preferred communities. Baltimore City has a lot of neglected communities that should have been a part of this process, areas that have a … are getting a glut of vacant properties. But, you know, ain’t nobody looking at. You know, instead they want to look at the other places. And of course they want to tear down everything, and, like the young lady said, concerned about gentrification — yeah, that’s what they’re making the way for.

GRANDPRE: My name is Lawrence Grandpre, I'm the director of research here at Leaders of a Beautiful Struggle. We go by LBS. We're a grassroots think tank here in Baltimore.

HELTMAN: I met Lawrence at the LBS offices in downtown Baltimore. And he said the fundamental problem with the city’s strategy — and, by extension, the prevailing revitalization strategy out there at the moment — is that it is focused on bringing in affluent buyers from elsewhere rather than empowering residents or attracting potential residents of more modest but solidly middle-class means.

GRANDPRE: Baltimore City has had a very specific redevelopment strategy that I call hunting the White Whale. Now, the White Whale is affluent individuals from a place like Washington, D.C., who can buy an expensive home in Baltimore City. And that expensive home would generate more property tax revenue. And these houses would appraise at a higher value, which will bolster not just the city's budget, but the city's perceived prestige and the city's perceived strengths. So a substantial, substantial part of Baltimore's housing strategy has been hunting these white whales, and I think to a substantial extent Baltimore, as of now, has largely failed in the effort of turning that into a sustainable strategy, long term, for reviving the masses of neighborhoods in Baltimore.

HELTMAN: Incidentally … that’s me he’s talking about. I’m one of those white whales. My family moved to Baltimore in 2015, in part because of price. And we love the city — my children were born here, and to us, it’s home. But he’s right — housing prices in Washington got us interested in Baltimore in the first place. Now, I don’t think anyone is telling me to go away, but the point he’s making is that perhaps the city shouldn’t be trying to find ways to attract another five to 10,000 me’s into the city. Because if the city is successful, and another couple of thousand me’s start showing up, that could create new problems.

GRANDPRE: Assuming there isn't a major financial bubble bursting, the next decade is going to see a massive wave of gentrification in Baltimore. And that gentrification will be framed as addressing the vacant housing dilemma, but I fear will be addressing it in the very market-centric way that does not take equity and the indigenous population as much into its account as it should be.

HELTMAN: This is what lies on the other side of the redevelopment coin: for all the discussion in Baltimore and other places about how hard it can be to reverse blight, to increase investment in a community, sometimes investment takes hold. And when it does, it can also take on a life of its own. And when that happens, it brings with it a whole other set of challenges. We’ll explore those next time, on Nobody’s Home.

“Brown in a Different Way”: The Gentrification Dilemma

GORDON: And I think … I was going to do this, like, right before you came, but I failed. But you take your time to set up.

HELTMAN: Are you ready?

GORDON: Sure. Let’s do it. With a baby on.

HELTMAN: With a baby.

GORDON: He’s pretty chill.

HELTMAN: Could you introduce yourself?

GORDON: Yeah. My name is Meghan Gordon, I’m a staff attorney at the East Bay Community Law Center, and I represent low-income communities in Alameda County, primarily doing eviction defense for low-income tenants.

HELTMAN: It’s January, and I’m in Alameda County, California, visiting Meghan, who graciously let me interview her one afternoon while she was on maternity leave.

Alameda County comprises much of the eastern portion of the San Francisco Bay area, and includes Berkeley and Oakland and is home to about 1.7 million people. It is also the site of one of the biggest real estate booms in recent memory.

I’ve been talking a lot about vacant housing — and that makes sense, it’s the subject of this podcast. But there is a challenge within the challenge when it comes to vacant housing, namely that even if a city or community is able to reverse the negative cycle of disinvestment within a community, that reversal can also spin out of control.

From American Banker, I’m John Heltman, and this is Nobody’s Home.

HELTMAN: In some ways, what is happening in Alameda County’s real estate market is representative of what can happen when housing markets go from cold to hot. That rapid increase in property values has the effect of reducing the number of vacant and abandoned properties, but it also has a secondary effect — and that is putting additional pressure on low-income tenants. Alameda County, like many urban jurisdictions, has rent control laws that limit a landlord’s ability to raise a tenant’s rent when market rates go up. The idea behind those laws is to ensure that longtime residents don’t get pushed out, but Meghan says unscrupulous landlords can find ways to get them to leave.

GORDON: Well, one thing that they'll do is, for example, there was a developer in Chinatown that did this, where they bought a building, and the tenants contacted a local organization that helped them organize and kind of fight back. And what did the landlord do? The landlord cut off the elevator, and said that they were doing, you know, construction and so they had to turn off the elevator. So a lot of people in this building are elderly and disabled. Now they can't get up and down. Then they tore out the bathrooms. So this was a building that was structured kind of like a single room occupancy, so, or like a dorm room, for example. So a lot of the tenants had their own individual space where they sleep and maybe they have a small kitchenette, but then they share bathrooms. So they tore out all the bathrooms except for one in the entire building. So now we've got tenants who are disabled who can't get out of the building and tenants who are getting UTIs because the lines for the bathrooms are so long. And you know landlords just, that's called, like, a constructive eviction. They make their property so horrible that they want tenants to just give up and leave. Some landlords will cut off the water. Some landlords will cut off gas. Some landlords will just ignore requests for repairs, thinking that once the tenant leaves — at least in this area, once of once your tenant moves out you can raise the rent to whatever you want when you get a new tenant, right?

HELTMAN: So you can cover the cost of whatever repairs need to be made but …

GORDON: Maybe. But a lot of people here in the Bay Area, because housing prices are so high, they will move into places that are uninhabitable because they have no other choice.

HELTMAN: And that’s just what is called “constructive” evictions. She says she gets cases from tenants whose landlords serve them with eviction notices that can’t be enforced, or threaten to call Immigration on tenants who they suspect of being undocumented. And she said the number of calls her agency gets for legal assistance with these evictions has gone up dramatically.

GORDON: I'd say that we're seeing not only more evictions but we're seeing evictions on a bigger scale, because there's so much money to be made by developers now. And every week there are mandatory settlement conferences set for eviction cases. And now we see anywhere from 30 to 50 evictions a week. Those are just cases that made it to trial to trial phase. So there are lots of cases where a landlord might file an eviction lawsuit and they never though tenant gets scared and moves out and so that doesn't even make it to the mandatory resettlement conference days so 30 to 50 evictions a week is a lot.

HELTMAN: That actually make it to trial.

GORDON: That are making it to, yeah.

HELTMAN: So it's not even, like, the number of evictions ...

GORDON: Yeah.

HELTMAN: ... there are a week ...

GORDON: Yeah.

HELTMAN: That's just the ones that don't get either settled or ...

GORDON: Exactly.

HELTMAN: ... otherwise kind of withdrawn.

GORDON: Yeah those are the ones where cases are filed and yeah they don't get settled. So there are tons of evictions where the landlord will file the eviction lawsuit and then maybe the tenant moves out before it gets set for trial. But then there are also cases where the tenant moves up before the landlord even files the eviction lawsuit. Maybe they get a notice from their landlord and that notice might be an illegal unlawful notice but they're scared. And so they move out or the landlord just harasses them into moving out. And so yeah 30 to 50 a week that we see this is just Alameda County and that is probably just the tip of the iceberg.

HELTMAN: And this phenomenon isn’t confined to the Bay Area.

WESTIN: Uh, Jonathan Westin director of New York Communities for Change. We're a community based organization working locally within low income communities of color across New York City and on Long Island. So we're mainly working in central Brooklyn, Southeast Queens, the South Bronx, upper Manhattan, and then some other places on Long Island. And our core focuses are around housing is probably our biggest focus.

HELTMAN: Like Alameda County, New York City has experienced a major upswing in property values in the last 30 years, and especially in the last 10 years. Jonathan says landlords are resorting to many of the same tactics to get rent-controlled tenants to leave.